What is oppositional defiant disorder?

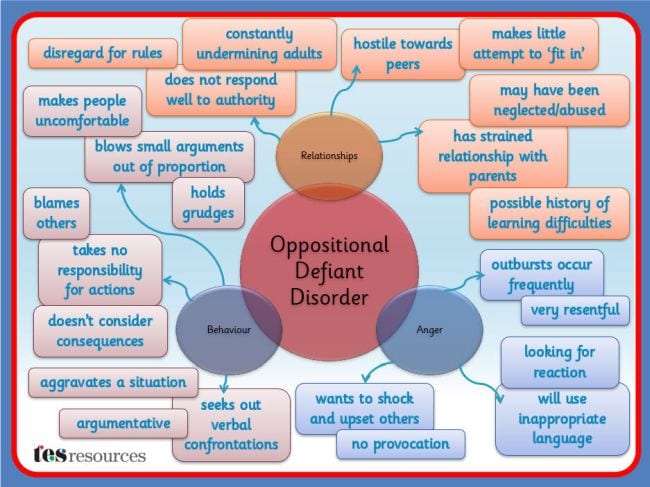

Source: TES Resources

Oppositional defiant disorder, commonly known as ODD, is a behavioral disorder in which children are—as the name suggests—defiant to the degree that it interferes with their daily lives. The DSM-5, published by the American Psychiatric Association, defines it as a pattern of angry, vindictive, argumentative, and defiant behavior lasting at least six months.

Now, chances are you’re probably thinking that kids of a certain age, especially toddlers and teenagers, are pretty much always arguing and defying. In fact, those can be appropriate behaviors at those ages, as kids test the world around them and learn how it works. However, ODD is a whole lot more than that, to the point where students with ODD disrupt their own lives and often the lives of everyone nearby.

Between 2–16 percent of the population may have ODD, and we’re not entirely sure of the causes. Scientists believe it could be genetic, environmental, biological, or a mix of all three. It’s diagnosed more often in younger boys than girls, though by their teen years both seem to be equally affected. It co-occurs in many kids with ADHD, with some studies indicating up to 50 percent of students with ADHD also have ODD.

What do students with ODD look like?

Source: Carolina Counseling Services

Kids with ODD push the limits of defiance far beyond reason. Their problem behavior is far more extreme than that of their peers, and moreover, it happens far more often.

Anger and irritability. These are the kids who seem angry all the time and fly off the handle at the slightest provocation. Their overreactions may devolve into temper tantrums, not just occasionally, but frequently. Therefore, every conversation you have with them seems to be a struggle.

Defiance and arguing. Most kids go through a phase where “no” is their favorite word, but for students with ODD, that phase never ends. They question everything, all the time, and consistently refuse to comply with rules and requests. Their need for argument may lead them to deliberately annoy others in an attempt to create conflict. However, they usually refuse to take responsibility for their mistakes or behaviors, blaming others for everything.

Vindictiveness. The ongoing anger of kids with ODD can lead to vindictiveness and a need for revenge. They are spiteful and retaliatory, holding grudges and demanding punishment for others.

Not surprisingly, these behaviors cause students with ODD to struggle both at home and in school. It’s hard for them to make friends, and their schoolwork often suffers, too. They may become depressed or anxious, or develop conduct or substance abuse disorders as they grow older. Early identification and treatment are vital to helping these kids.

How is ODD treated?

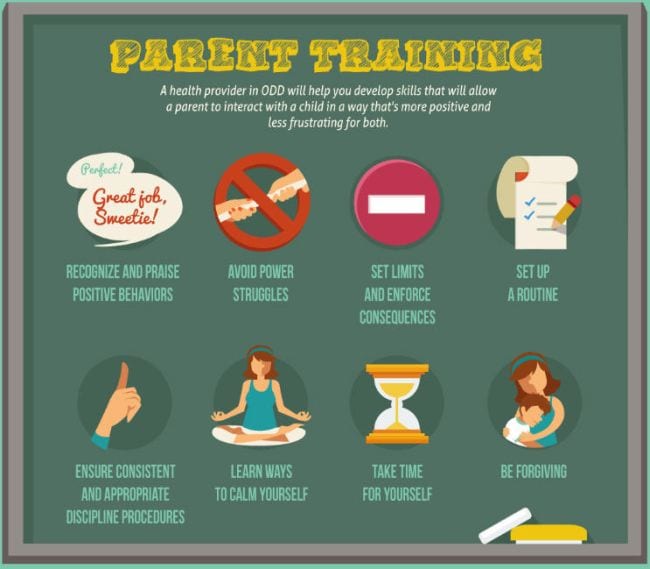

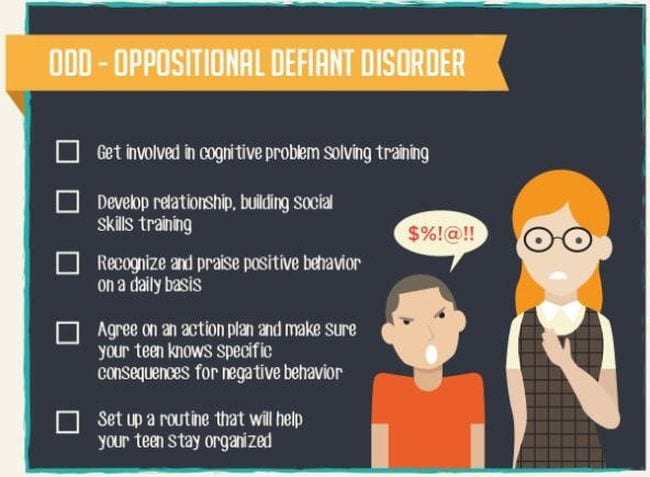

Source: Manhattan Psychology Group; see full infographic here

Therapy and behavior modification are most important in treating oppositional defiant disorder. Parents and their kids undergo counseling and behavioral therapy to learn to create a better home environment. They work to reinforce good behavior and break the cycles that lead to the same arguments and problems over and over again.

Teachers may be asked to help with these therapies by reinforcing what parents are doing at home. As with any behavior problem, it’s important to be consistent in how the adults in their lives interact with kids with ODD.

How do I help students with ODD?

Oppositional defiant disorder is incredibly frustrating for teachers, who are often already dealing with a variety of behavioral issues that are usual in kids anyway. We asked experienced teachers in the WeAreTeachers Helpline group on Facebook for their best methods for helping students with ODD. Here’s what they said.

Avoid power struggles.

Most of our teachers agreed: Stay out of those winless power struggles. As Kris W. said, “Pick your battles. A student of mine corrects me all the time, whether I am wrong or not. I answer back, ‘OK, let’s double-check that.’ If I made a mistake, I correct it, and we move on; if he’s wrong, I silently let him to figure it out.”

Be consistent.

In these situations, consistency is key. “Instead of arguing, repeat your words and consequences,” says Brandy T. “I use trigger words that I often repeat so the student knows I mean business. If a student tries to argue, I simply say either ‘not now,’ ‘later,’ or ‘fix the issue!’ The student then knows they can go to their chill-out space if they need to calm down.”

Give them choices.

Kids with ODD are looking for control. Rather than letting them drive the situation, you can give them a feeling of control while maintaining control yourself. “Always give choices,” advises Holli A. “State your choices—then walk away. Give the student time to process and decide which choice to make. If they don’t like the choices, don’t engage. If they try to argue, then repeat the choices and walk away again. If the student still will not choose, they do not get to participate in their preferred activity.”

As in other situations, it pays to stay consistent in your classroom rules and discipline. “After I give choices, I always reinforce the classroom rules and procedures and follow up with an appropriate consequence,” says Kristel R. “You cannot falter; stick to your rules and follow through.”

Give them space to reset.

Kids with ODD can learn to recognize when they’re feeling overwhelmed and getting ready to challenge or defy. Giving them a safe space to calm down and rethink their choices can be beneficial. “Put out books, coloring, LEGO bricks, etc., in a place where they can go on their own when they feel like they need a break,” says Tobey G. “Often immediately after activities with a lot of stimulation, these kids need a safe space to calm down. Let them decide if and when they need to excuse themselves.”

Offer positive reinforcement and appropriate rewards.

Kids with ODD often respond to positive behavior reinforcement. It’s helpful to offer them a chance to earn certain privileges, rather than taking those privileges away as punishment. For instance, give them the ability to earn screen time when they promptly do as they’re asked, instead of threatening to take away screens when they defy.

When using a reward system, make sure that it is appropriate and isn’t perceived as manipulation. Leslie L. uses a behavior tracking system and a reward system where students that can turn in for an incentive (iPad time, lunch with a teacher, etc.). “I also build breaks right into their schedule,” adds Leslie. “And I try to be as patient and understanding as I possibly can.”

Teacher Erica M. also uses a point system checklist with options A & B. If they do each one, they earn “points” for an incentive, which often is iPad time during the last 15 minutes of class. “Find an interest and use that to your advantage!” Erica says.

Make personal connections.

Often kids with ODD are looking for a relationship with a teacher who can help them deal with problems on their own instead of making them stand out in a negative way. Building a connection with them will help get to the root of the behavior.

“Almost all of my students have ODD, and I have a great relationship with most of them,” says Kendra J. “Find out what they are interested in and have conversations on their level during breaks.” Allow them to set goals and decide together what the consequences will be if they don’t meet the goal.

Carol H. says, “Find something at the student’s interest level. I once had a middle school girl that hated all of her teachers and was out of control. She would curse at adults and peers, scratch, bite, and refuse to complete work. I found out she played soccer for a travel team. So did my son. A few weeks into the school year, she had a game adjacent to my son’s, and I was able to watch her play. It changed everything. She is a freshman in college now, and we still keep in touch.”

Add a comment